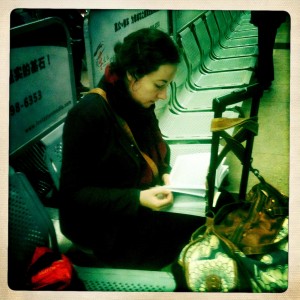

The overnight train from Hong Kong to Shanghai was very comfortable and fast, a pretty standard sleeper train that goes at 160km/h with four person berth cabins, a toilet at the end of the corridor and an open plan sink area with two basins at the other (which oddly usually became a hang out for the married males in the carriage). We were soon joined in our cabin by a lovely Chinese couple who helped us to more accurately map out our exact route forwards through China and shared their steaming flask of green tea with us (hot water is available on tap on all Chinese trains and everyone tends to carry a Thermos with an inbuilt tea strainer). The journey would take us a mere 20 hours to pass through 1,991 km, though this is not as fast as the new High Speed link between Beijing and nearby Shenzhen (making it the world’s longest high-speed railway line) which opened in December 2012.

The overnight train from Hong Kong to Shanghai was very comfortable and fast, a pretty standard sleeper train that goes at 160km/h with four person berth cabins, a toilet at the end of the corridor and an open plan sink area with two basins at the other (which oddly usually became a hang out for the married males in the carriage). We were soon joined in our cabin by a lovely Chinese couple who helped us to more accurately map out our exact route forwards through China and shared their steaming flask of green tea with us (hot water is available on tap on all Chinese trains and everyone tends to carry a Thermos with an inbuilt tea strainer). The journey would take us a mere 20 hours to pass through 1,991 km, though this is not as fast as the new High Speed link between Beijing and nearby Shenzhen (making it the world’s longest high-speed railway line) which opened in December 2012.

The route out of Hong Kong led us through lush hills and spacious hilltop villas, which shortly transformed into high-rise urban sprawl when we reached the border with Shenzhen (we spotted some fairly quirky architecture in this city – from elephant-shaped shopping centres to castle-turreted restaurants) . After a good night’s sleep we were woken in the morning to the sounds of classical music played through a speaker in the cabin and corridors, which progressively increased in volume as we approached our destination. We felt fairly relaxed by the time we reached Shanghai, which was lucky because the break in travelling had lulled us into a false sense of security and we had forgotten to write down the address of our hostel in Chinese. It was raining and the queue at the taxi rank was long, but luckily someone in the queue was able to help us out by translating the street address.

. After a good night’s sleep we were woken in the morning to the sounds of classical music played through a speaker in the cabin and corridors, which progressively increased in volume as we approached our destination. We felt fairly relaxed by the time we reached Shanghai, which was lucky because the break in travelling had lulled us into a false sense of security and we had forgotten to write down the address of our hostel in Chinese. It was raining and the queue at the taxi rank was long, but luckily someone in the queue was able to help us out by translating the street address.

We had booked into the Phoenix Hostel, a short walk from Dashijie station (Chinese: 大世界站; pinyin: Dàshìjiè Zhàn), The Bund and People’s Square (Chinese: 人民广场站; pinyin: Rénmín Guǎngchǎng Zhàn). This is a great hostel with a fantastic and reasonably-priced restaurant on its ground floor (we thoroughly recommend the mushroom dumplings). We spent the first day getting our bearings by walking around the district and finding our way to The Bund (parallel to the Zhonshang road) – previously a British concession and financial power base and now an embankment of preserved historical buildings in Shanghai where building heights are restricted. After a period of intentional neglect during the post-war communist era, Shanghai came under the spotlight again in the ’90s when it was selected as the show-ground for China’s reform and new economy. Consequently, it is now both China’s largest and richest city and it has gone to some lengths to rival Hong Kong’s famous harbour-front light displays along its own affluent riverside stretch.

Not only is every building bordering the Huangpu river and every boat on it lit up at night but so are the city’s highways, under-lit by a dazzling UV light which seems to epitomise the city’s Blade-Runner-esque futuristic

Not only is every building bordering the Huangpu river and every boat on it lit up at night but so are the city’s highways, under-lit by a dazzling UV light which seems to epitomise the city’s Blade-Runner-esque futuristic  aesthetic.

aesthetic.

The Bund, by contrast, offers a throwback glance to the city’s days of colonial concession where European powers such as Britain, France, Germany and the Netherlands as well as America, Russia and Japan were apportioned areas of territory in the city under the terms of a series of unequal treaties. The British, who controlled The Bund (later with America), made it a playground for the amassing and spending of their financial riches from the East, erecting gothic and baroque style corporate buildings and hotels along the waterfront along with clubs, Cathedrals and huge mansions for their hedonistic exploits in and around the wider city (J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun and Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton evocatively depict expatriate life in the city in the lead up to its occupation by the Japanese during WW2).

The British, who controlled The Bund (later with America), made it a playground for the amassing and spending of their financial riches from the East, erecting gothic and baroque style corporate buildings and hotels along the waterfront along with clubs, Cathedrals and huge mansions for their hedonistic exploits in and around the wider city (J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun and Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton evocatively depict expatriate life in the city in the lead up to its occupation by the Japanese during WW2).

I’ve read a number of accounts from people returning to Shanghai on J.G. Ballard’s trail who find themselves dismayed when faced with the fact that his house, 31a Amherst Avenue, has now been gutted and turned into a wine bar/restaurant. The current battle lines of Shanghai – drawn between preservation and development - also point to a battle of histories and the question of whose ‘past’ merits preservation, if any. The name J.G. Ballard means nothing to the current owners of 31 Amherst who see it as a prime business location and nothing else; the government seem keen to support this view on the whole and even if a building is heritage listed not much can be done to prevent it from being developed if the right money changes hands. Shanghai seems keen to reinvent rather than preserve its past, rejecting anything which may hold it back in its quest for ultra modernisation.

Having said this, there are still plenty of concession era remnants around the city left standing – The Bund being an obvious place to start with most of its flagship buildings still intact – the iconic Sassoon Mansion or Peace Hotel is particularly worth looking out for given that it has survived in purpose as well as structure. The next best place to walk through is the old French quarter (a foreign concession until 1946) where spacious tree-lined boulevards and low rise 1930′s style housing still abound. The famous Art Deco Cathay Theatre on Avenue Joffre (Huaihai rd) is an obvious port of call – it is still a cinema and is famous today for its screenings of low budget art house films.

Having said this, there are still plenty of concession era remnants around the city left standing – The Bund being an obvious place to start with most of its flagship buildings still intact – the iconic Sassoon Mansion or Peace Hotel is particularly worth looking out for given that it has survived in purpose as well as structure. The next best place to walk through is the old French quarter (a foreign concession until 1946) where spacious tree-lined boulevards and low rise 1930′s style housing still abound. The famous Art Deco Cathay Theatre on Avenue Joffre (Huaihai rd) is an obvious port of call – it is still a cinema and is famous today for its screenings of low budget art house films.

The French district is still characterized by its long, tree peppered boulevards and it also remains a hub for ex-pats as there are many art shops, cafés, bars and cinemas here.

The French district is still characterized by its long, tree peppered boulevards and it also remains a hub for ex-pats as there are many art shops, cafés, bars and cinemas here.

Not long after we arrived on the Fuxing Lu road, we came across two French girls wheeling their bikes along the pavement, who later told us that they were both working in Shanghai. They volunteered to show us around and took us to some of their favourite spots which included the café Bikes and Friends – famous for its chips, wines and film nights. The café was full of young Australians, Germans and French people when we arrived – many of whom were currently working in Shanghai (we spoke to a couple of them who seemed nostalgic for their homes and said that the Café was run by a Chinese businesswoman who let them create a little piece of it here in the café).

Not long after we arrived on the Fuxing Lu road, we came across two French girls wheeling their bikes along the pavement, who later told us that they were both working in Shanghai. They volunteered to show us around and took us to some of their favourite spots which included the café Bikes and Friends – famous for its chips, wines and film nights. The café was full of young Australians, Germans and French people when we arrived – many of whom were currently working in Shanghai (we spoke to a couple of them who seemed nostalgic for their homes and said that the Café was run by a Chinese businesswoman who let them create a little piece of it here in the café). After a couple of drinks the girls walked with us a little further and dropped us outside a gated club called the YongFoo Elite; they told us that it’s an exclusive dining club housed in the building and grounds of the old British consulate. They told us it was well worth exploring and even though we felt under-dressed they advised us to walk in confidently and say we were meeting someone for tea (you don’t actually have to buy anything to look around the gardens).

After a couple of drinks the girls walked with us a little further and dropped us outside a gated club called the YongFoo Elite; they told us that it’s an exclusive dining club housed in the building and grounds of the old British consulate. They told us it was well worth exploring and even though we felt under-dressed they advised us to walk in confidently and say we were meeting someone for tea (you don’t actually have to buy anything to look around the gardens).  We proceeded up the driveway and soon saw a British-looking house partially covered by a pine tree. We felt as if we had entered another country in another century. Ornamental ponds of coy carp sat alongside English barber chairs, American vintage fridges, French chaise longues and Indian garden beds. It was very peaceful and serene, the only sound coming from garden birds and the well-dressed Chinese men and women quietly taking tea on the Art Deco patio. For all its modernisation, I suddenly felt like I really had stepped back in time in Shanghai:

We proceeded up the driveway and soon saw a British-looking house partially covered by a pine tree. We felt as if we had entered another country in another century. Ornamental ponds of coy carp sat alongside English barber chairs, American vintage fridges, French chaise longues and Indian garden beds. It was very peaceful and serene, the only sound coming from garden birds and the well-dressed Chinese men and women quietly taking tea on the Art Deco patio. For all its modernisation, I suddenly felt like I really had stepped back in time in Shanghai:

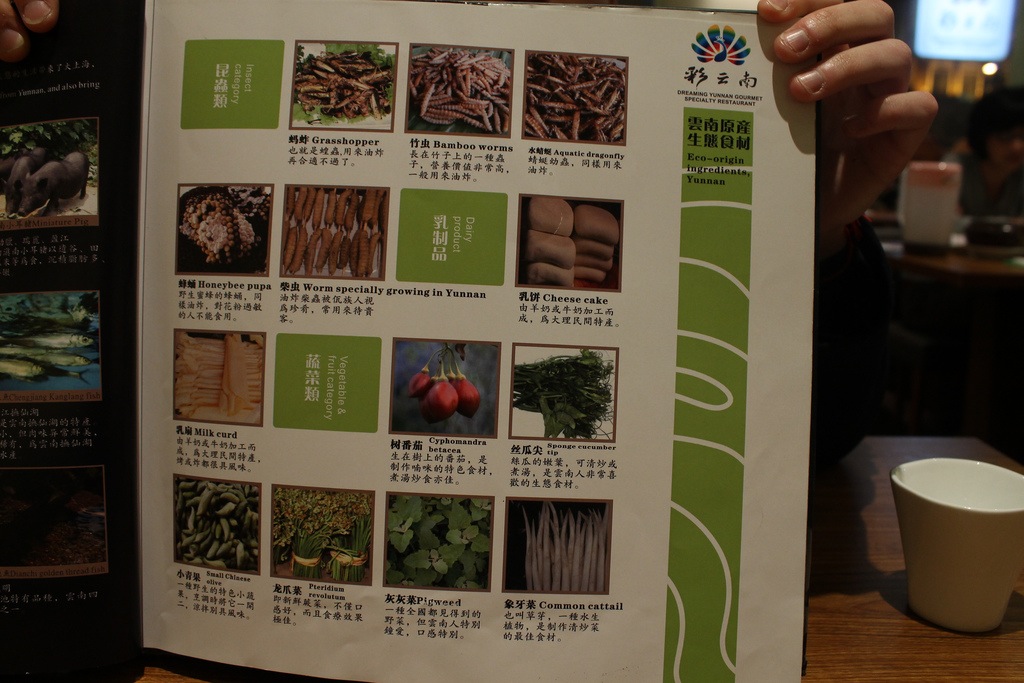

Alongside fashionable clubs and bars such as the YongFoo Elite, Shanghai is also fast making a name for itself in world class dining and as in Hong Kong, you can find most types of cuisine here.  We were lucky enough to find a very interesting restaurant down the road from us, which specialised in food from Yunnan, called “Dreaming Yunnan Gourmet Specialty Restaurant” (a particluarly popular type of Chinese cuisine in Shanghai). Ingredients are central to the menu choice here and you can choose every aspect of your dish from ‘roots’ to ‘drug herbs’. We played it fairly safe – opting for vegetable based dishes such as the yellow mashed potato with blueberry and the Taro with fragrant willow. The restaurant also served a variety of fried larvae and worms, a regional taste that we decided we’d give a miss this time around.

We were lucky enough to find a very interesting restaurant down the road from us, which specialised in food from Yunnan, called “Dreaming Yunnan Gourmet Specialty Restaurant” (a particluarly popular type of Chinese cuisine in Shanghai). Ingredients are central to the menu choice here and you can choose every aspect of your dish from ‘roots’ to ‘drug herbs’. We played it fairly safe – opting for vegetable based dishes such as the yellow mashed potato with blueberry and the Taro with fragrant willow. The restaurant also served a variety of fried larvae and worms, a regional taste that we decided we’d give a miss this time around.

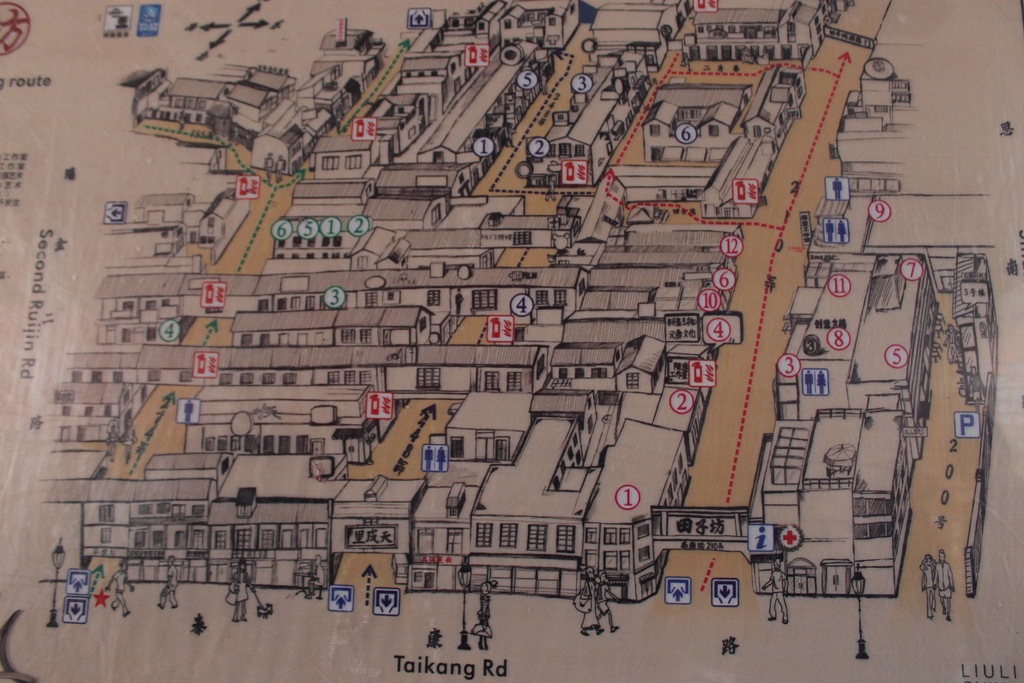

Before we left Shanghai for further rural explorations, we were keen to visit the sprawling arts district known as Tian Zi Fang. The area is largely hidden from the neon-pulsing shopping streets that surround it, and it took us a little time to locate the entrance on Lane #274. Rows and rows of narrow, pedestrianised streets hide beautiful textile and ceramic shops, a microcosm of world cuisine and some of the most fascinating tea shops we’ve ever seen. Thanks to areas like this, Shanghai is becoming synonymous with cutting-edge art, fashion and design that blends ancient crafts and traditions involving scent, taste and patience with new technique and aesthetic. It is also the chosen hangout spot of Shanghai’s young set who break up their shopping in the districts’ quirky courtyard bars.

Before we left Shanghai for further rural explorations, we were keen to visit the sprawling arts district known as Tian Zi Fang. The area is largely hidden from the neon-pulsing shopping streets that surround it, and it took us a little time to locate the entrance on Lane #274. Rows and rows of narrow, pedestrianised streets hide beautiful textile and ceramic shops, a microcosm of world cuisine and some of the most fascinating tea shops we’ve ever seen. Thanks to areas like this, Shanghai is becoming synonymous with cutting-edge art, fashion and design that blends ancient crafts and traditions involving scent, taste and patience with new technique and aesthetic. It is also the chosen hangout spot of Shanghai’s young set who break up their shopping in the districts’ quirky courtyard bars.

Inspired by the tea tasting rooms of Tian Zi Fan, we decided to make Hangzhou and its nearby Longjing tea plantations our next destination (we were told that with any luck we’d just be in touch for the picking of the first flush), so with some reluctance we booked our onward train…

Inspired by the tea tasting rooms of Tian Zi Fan, we decided to make Hangzhou and its nearby Longjing tea plantations our next destination (we were told that with any luck we’d just be in touch for the picking of the first flush), so with some reluctance we booked our onward train…