We were both a bit apprehensive about the transatlantic voyage (given that this time last year we would both rather have swum through shark-infested waters than taken a cruise liner). As someone we’ve met along the way so far aptly said, ‘they just seem so fake’ and having dipped into Gwyn Topham’s book Overboard: The Stories Cruise Lines Don’t Want Told, which looks into the darker side of cruising, I was more than sceptical. Friends tried to reassure us with the helpful advice that it will be a great chance to see what goes on from the inside and that we can make of the experience whatever we want. So, with that in mind, we said goodbye to our parents at a grey and rainy Ocean terminal in Southampton and boarded the Queen Mary II.

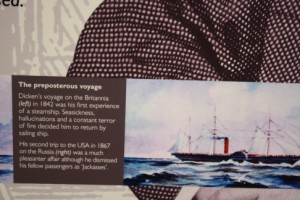

My first observation was that it was really like a floating hotel (and not the kind we would usually stay in) but our fellow passengers seemed nice and not at all the pretentious sort of people we’d been dreading that we’d find on board. Although we’d paid for the lowest grade of cabin, we’d been upgraded to a balcony (which apparently sometimes happens when you mark down that this is you first transatlantic trip with Cunard in the hope that you’ll become a frequent traveller). Our parents had gathered in the car park below so we had about half an hour of small specks waving to small specks before the boat blew its horn and slowly left the dockside for the English Channel/La Manche. Lots of smaller sailing ships clustered around and sailed alongside the boat as far as Hamble-le-Rice and we couldn’t help but enter the spirit of the voyage and think of all those people who had done it before us (I had just begun reading Colm Toíbín’s Brooklyn where an Irish girl had just embarked on her journey to the ‘land of opportunity’ in search of a job). We were later to discover info boards and galleries dedicated to past passengers all around the ship, displaying pictures of Ginger Rogers, Elizabeth Taylor and Charlie Chaplin on board various Cunard liners and less than raving quotes from Dickens and Wilde about their respective voyages (I get the impression that if they had been able to fly instead of sail, they probably would have).  In reality, it was clear that the glamorous heyday of the transatlantic voyage – where to see and be seen by those ‘who count’ was everything – was well and truly over (to my knowledge, guests are no longer given booklets listing the important dignitaries, aristocrats and movie stars who will be on their sailing). Instead, what we found were approachable, interesting people of all ages and from an array of countries (Russia, Turkey, Latvia, Romania, England, France, America, Japan, Poland…) all on individual quests and adventures. A number of people we spoke to were emigrating from various places in Europe to America, carrying with them their life packed into seven suitcases or less and even their cats and dogs

In reality, it was clear that the glamorous heyday of the transatlantic voyage – where to see and be seen by those ‘who count’ was everything – was well and truly over (to my knowledge, guests are no longer given booklets listing the important dignitaries, aristocrats and movie stars who will be on their sailing). Instead, what we found were approachable, interesting people of all ages and from an array of countries (Russia, Turkey, Latvia, Romania, England, France, America, Japan, Poland…) all on individual quests and adventures. A number of people we spoke to were emigrating from various places in Europe to America, carrying with them their life packed into seven suitcases or less and even their cats and dogs , of which there were several on board (they were walked around the top deck daily). One American journalist said he was now a frequent transatlantic passenger as he no longer trusted airport security while a few others were frightened of flying (but most frequent passengers either did the trip twice a year or less or had their passage subsidised by work). Some were on board for more personal reasons, one elderly gentleman reliving his trip as a 14 year-old boy on the original Queen Mary, where he had ‘first fallen in love’, another ac

, of which there were several on board (they were walked around the top deck daily). One American journalist said he was now a frequent transatlantic passenger as he no longer trusted airport security while a few others were frightened of flying (but most frequent passengers either did the trip twice a year or less or had their passage subsidised by work). Some were on board for more personal reasons, one elderly gentleman reliving his trip as a 14 year-old boy on the original Queen Mary, where he had ‘first fallen in love’, another ac companying her mum who had worked on the original Queen M.

companying her mum who had worked on the original Queen M.

Most days we woke up and could see nothing from our balcony, the whole ship being enshrouded by a persistent transatlantic mist which barely cleared all day.  On board there were distractions in the form of lectures on the bird and marine life of the Grand Banks (a shallow area of the Atlantic, one day’s travel East of New York); the architecture of New York; shipping through the years; navigation and a trio of presentations given by Geoffrey Howe, the ex-Deputy Prime Minister who famously fell out with Thatcher in the mid-eighties, ultimately leading to the collapse of her government. Some talks were more interesting than others and in one seminar a rather fraught debate was sparked about about the Wikileaks ‘scandal’ much to our amusement although it was unfortunately shut down by the compère before it could get too interesting.

On board there were distractions in the form of lectures on the bird and marine life of the Grand Banks (a shallow area of the Atlantic, one day’s travel East of New York); the architecture of New York; shipping through the years; navigation and a trio of presentations given by Geoffrey Howe, the ex-Deputy Prime Minister who famously fell out with Thatcher in the mid-eighties, ultimately leading to the collapse of her government. Some talks were more interesting than others and in one seminar a rather fraught debate was sparked about about the Wikileaks ‘scandal’ much to our amusement although it was unfortunately shut down by the compère before it could get too interesting.

As we began to avoid the formal dinners and spend more time reading and going to lectures it felt a little bit like being back at school or university, only with better food. The ship’s crew (who mainly seemed to come from Romania, Latvia, Poland and the Philippines) were really friendly and interesting people and we got to know a few of them quite well. One lovely girl that we talked to had been wor king as an accountant and had given up her job at home to work on the ship, travel and see things beyond her four office walls. She was really loving it so far (even though they have to work very long shifts) and said she was ‘so glad to have made the decision’. On the boat, we were essentially a travelling community and we were really glad to have had the opportunity to get to know the people we were travelling with much better than we would have otherwise. I can’t even remember the last time I spoke to a stranger in depth on a plane journey. A central part of our slow travel experience so far has definitely been about connecting with our environment and the people around us in a more meaningful way.

king as an accountant and had given up her job at home to work on the ship, travel and see things beyond her four office walls. She was really loving it so far (even though they have to work very long shifts) and said she was ‘so glad to have made the decision’. On the boat, we were essentially a travelling community and we were really glad to have had the opportunity to get to know the people we were travelling with much better than we would have otherwise. I can’t even remember the last time I spoke to a stranger in depth on a plane journey. A central part of our slow travel experience so far has definitely been about connecting with our environment and the people around us in a more meaningful way.

Each day (bar one or two) we had to set our clocks back one hour, meaning that we very gradually adjusted to the time difference and would suffer no ‘jet lag’ at the other end. The boat was so big that any feelings of cabin fever were easy to combat – we often joined the joggers on their kilometre-long circuits around the boat if we needed some air and could easily find quiet corners where we’d see no one else for hours (especially on the foggy days) if we  needed some space. About five days in, just as we were entering the Grand Banks off the coas

needed some space. About five days in, just as we were entering the Grand Banks off the coas t of Nova Scotia, we woke up to clear skies and sunshine, the first we’d seen in a while given the weather we’d left behind in England. It sounds clichéd but the water really was like glass. We headed for our favourite spot, the observation deck underneath the bridge on deck 11, and were lucky enough to sight whales (Minke appare

t of Nova Scotia, we woke up to clear skies and sunshine, the first we’d seen in a while given the weather we’d left behind in England. It sounds clichéd but the water really was like glass. We headed for our favourite spot, the observation deck underneath the bridge on deck 11, and were lucky enough to sight whales (Minke appare ntly), pods of common dolphins, common seals (which are not actuall

ntly), pods of common dolphins, common seals (which are not actuall y that common any more), sharks and even a Sunfish. The realisation that in the past, we’ve flown over all this in a matter of hours, barely thinking about any of the life we were passing over, added a new dimension to our slow journey.

y that common any more), sharks and even a Sunfish. The realisation that in the past, we’ve flown over all this in a matter of hours, barely thinking about any of the life we were passing over, added a new dimension to our slow journey.

We finally arriv ed in New York, 7 days after departure from Southampton, at 4.30 am, just in time to see the boat pass very narrowly under the bridge. As the sun rose over

ed in New York, 7 days after departure from Southampton, at 4.30 am, just in time to see the boat pass very narrowly under the bridge. As the sun rose over  Manhattan and Brooklyn, and we watched the night time lights on the statue of liberty and sky scrapers extinguish, it was difficult to say that romance and the transatlantic crossing is completely dead.

Manhattan and Brooklyn, and we watched the night time lights on the statue of liberty and sky scrapers extinguish, it was difficult to say that romance and the transatlantic crossing is completely dead.

Facts and Figures

Typical Food Stores List for a Six Day Voyage includes:

13,200 packets of cereal

30,000 tea bags

1,230 lbs of coffee

3,200 lbs of butter

36, 720 eggs

1,525 gallons of milk

11 tonnes of potatoes

6,500 lbs of flour

4000 lbs of rice

690 ltrs of spirits

200 pcs of Cigars and 3,200 pkts of Cigarettes

Fuel Consumption

- Diesel Engines – 3.1 tonnes/hour of Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) at 100% Load

- Gas Turbines – 6.0 tonnes/hour each of Marine Gas Oil (MGO) at 100% Load

Daily consumption at a speed of 29 knots, depending on the sea state and wind, is approx 261 tonnes of HFO for the diesel engines and 237 tonnes of MGO for the gas turbines

Maximum propulsion power is 86.0 MW – equivalent to 115,328 HP

Speed

Total journey time – approx 160 hours; approx speed 28.5 knots (33 mph).

Total distance from Southampton – NY = 5909 kilometers (3190 nautical miles)

Passenger numbers.

Passenger capacity – normally 2620 (max. 3090) plus approx 1300 crew

Emissions

We are not going to pretend that ‘luxury’ cruise travel of this kind is much better carbon emissions-wise than taking a flight over the same distance. George Monbiot for one has highlighted that luxury cruise travel is hugely emitting and the tonnes of carbon dioxide produced on a transatlantic voyage per passenger are comparable to taking a flight. However, the one big difference between these two modes of transport is that a boat takes seven days to reach its destination, whereas a plane can complete the journey and back again seven times in the same period, ultimately carrying around the same number of people in total as the boat on its one journey. A boat can also allow you to stop off at points along the way, which for a plane would result in a steep increase in emissions due to the fact that a considerable quantity of these are created during take-off and landing (which is why long haul flights are ironically better for the environment per mile than short haul). Although we will ultimately be covering more miles on this trip by slow train than by boat (hopefully reducing our overall carbon emissions), we are aware that travelling the world was always going to result in higher emissions than holidaying within the UK or Europe by train. We are viewing this trip as a once in a life time journey and we wanted to be able to experience on that journey the expanse of every passing mile and ultimately to appreciate the distance we have travelled.

Other Measures

We asked someone how cruise lines are dealing with the criticism they have received from environmental groups regarding dumping waste and fuel usage. They said measures have been introduced to combat these and each boat now has an environmental officer on board. Measures installed so far include:

Fresh Water Production

Water production from sea water is by 3 x Alfa Laval Multi Effect Plate Evaporators each producing 630 tonnes/day. Water is used for showers, washing (for guests and for the deck) and cooking.

Steam

Steam is produced by 2 x Saacke Oil fired boilers and by exhaust gas economisers by using waste heat from the Diesel Engine and Gas Turbine exhausts. Steam is used for accommodation heating, laundry heating, fuel oil heating and for steaming food in the galleys.

There is clearly a long way to go and the sheer amount of food consumed for one, was difficult to rationalise but this is a start at least.