The outer city high-speed rail terminal of Shanghai came as something as a surprise to us, though given the investment China has been inputting into its rail links over the past few years it probably shouldn’t have. It was light, bright, and shiny with something of a deserted airport feel to it (there was hardly anyone around which made a change from the crowds of Shanghai). Its postmodern concourse was vast and glassy, and the wide open ground floor space was flanked by a top floor of restaurants and little stalls selling expensive freeze-dried noodles and cakes. From here you can reach most of the major cities in China by direct train, and the number of high-speed routes seems to be increasing year-on-year.

The outer city high-speed rail terminal of Shanghai came as something as a surprise to us, though given the investment China has been inputting into its rail links over the past few years it probably shouldn’t have. It was light, bright, and shiny with something of a deserted airport feel to it (there was hardly anyone around which made a change from the crowds of Shanghai). Its postmodern concourse was vast and glassy, and the wide open ground floor space was flanked by a top floor of restaurants and little stalls selling expensive freeze-dried noodles and cakes. From here you can reach most of the major cities in China by direct train, and the number of high-speed routes seems to be increasing year-on-year.

The distance between the Shanghai and Hangzhou is 177 kilometres, but we got there in under an hour, travelling at 300km/h. This was our first experience on a High-Speed Train in China and its speed (in comparison to the open windows and gentle motion of the trains we had taken in South East Asia) was something of a shock – though we managed to take a few mildly blurry shots with our camera.

Once we pulled out of the station, the fringe of Shanghai’s vast suburban construction belt soon came into view. The evidence of fast expansion was hard to miss and we passed hundreds of small apartment blocks built in neatly arranged streets, in addition to slightly less sturdy looking housing blocks surrounding construction sites (perhaps for the people working on them). Considering that the city is still growing at a rate of a million people a decade, this construction is probably necessary but it was almost difficult to detect where the urban sprawl of Shanghai stopped and Hangzhou began.

We arrived in Hangzhou in the late afternoon, expecting to find a little tourist town surrounded by tea plantations. Our research should have been more thorough: the centre of Hangzhou is less of a country retreat and more of a sprawling metropolitan city housing 4 million people. When tourists speak of Hangzhou they are more than likely referring to the lake and ‘People’s Pleasure Garden’ which is about a fifteen to twenty minute bus ride from the city centre. After getting stuck in a long queue of traffic on the lake road (which is nearly always backed up with fuming coaches carrying daytrippers from the surrounding cities) we eventually got to our hostel which was located a few minutes walk from the famous “West Lake”.

We arrived in Hangzhou in the late afternoon, expecting to find a little tourist town surrounded by tea plantations. Our research should have been more thorough: the centre of Hangzhou is less of a country retreat and more of a sprawling metropolitan city housing 4 million people. When tourists speak of Hangzhou they are more than likely referring to the lake and ‘People’s Pleasure Garden’ which is about a fifteen to twenty minute bus ride from the city centre. After getting stuck in a long queue of traffic on the lake road (which is nearly always backed up with fuming coaches carrying daytrippers from the surrounding cities) we eventually got to our hostel which was located a few minutes walk from the famous “West Lake”.

It was one of the first hot days we had experienced in China so far and so we waited until evening to really explore our surroundings. After the majority of the day tourists had gone home, we found the lake to be rather beautiful and peaceful. It helped that all the magnolias had started to blossom leaving a wonderful scent in the air at dusk. The West Lake itself is pretty big and it takes about two hours to walk all the way around it so we decided to leave that for another day.

It was one of the first hot days we had experienced in China so far and so we waited until evening to really explore our surroundings. After the majority of the day tourists had gone home, we found the lake to be rather beautiful and peaceful. It helped that all the magnolias had started to blossom leaving a wonderful scent in the air at dusk. The West Lake itself is pretty big and it takes about two hours to walk all the way around it so we decided to leave that for another day.

The next morning we were awoken at 6am to the sounds of Big Ben chiming. It took me a while to remember where I was and with bleary eyes, I opened the blind in our attic hostel room to find a schoolyard below and groups of children lining up in a very orderly fashion to the sound of the bell. The children then began to sing (a mixture of English and Chinese songs), making it impossible to go back to sleep, so we decided to head out for the day.

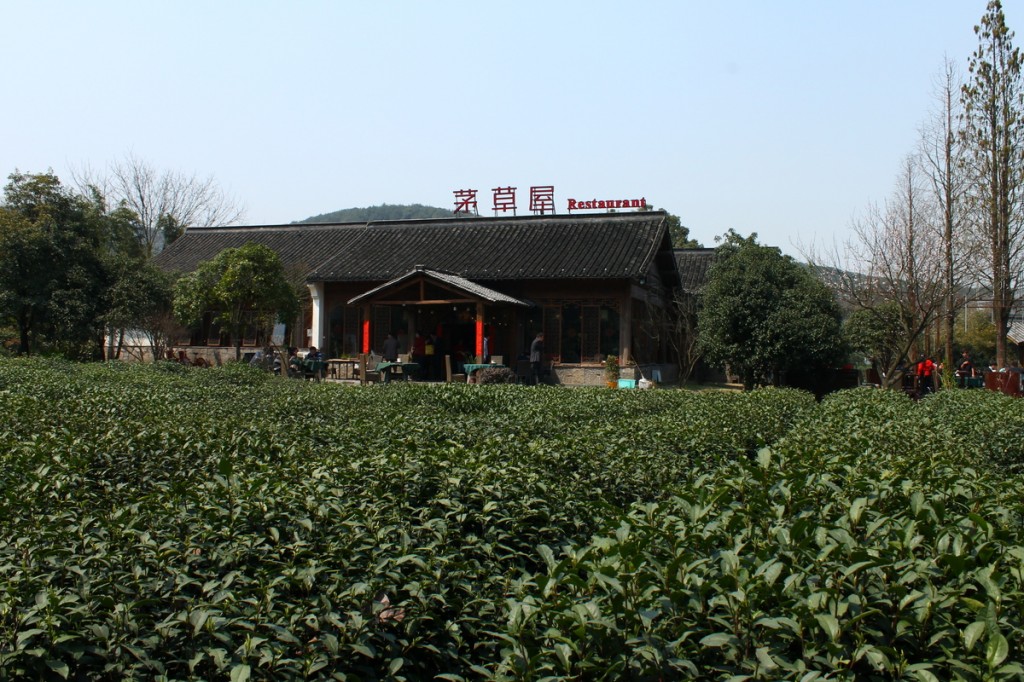

The next morning we were awoken at 6am to the sounds of Big Ben chiming. It took me a while to remember where I was and with bleary eyes, I opened the blind in our attic hostel room to find a schoolyard below and groups of children lining up in a very orderly fashion to the sound of the bell. The children then began to sing (a mixture of English and Chinese songs), making it impossible to go back to sleep, so we decided to head out for the day.  As we were up early, we asked some people in the hostel about journeying up to the Lion’s Peak of Hangzhou, where Lóngjǐng (translated in English as Dragon Well), one of the most famous teas in China, is grown. What’s more, we had heard that the picking of the highly valued first flush had just begun and if we visited the right pickers we might be able to buy some at an affordable price. Luckily there was a bus stop just near the hostel along the West Lake road and about half an hour later a bus with some vines painted onto its side pulled up – so we were pretty sure it was the right one. We weren’t entirely confident as to where we should get off so we slightly winged it and travelled through a few villages, where we could see people returning from their early morning tea pickings with the leaves balanced in baskets on their heads. About 10 minutes later, the bus stopped ascending and the land flattened out with miles and miles of tea plantations before us. The bus came to a stop and as we realised we were almost the on only ones left on it, we decided that this was as good a spot as any to explore from. It was the right choice as we found ourselves conveniently outside the Green Tea restaurant, which we had heard about from someone in Shanghai. The queues outside were already forming so we decided to take a ticket and try it out.

As we were up early, we asked some people in the hostel about journeying up to the Lion’s Peak of Hangzhou, where Lóngjǐng (translated in English as Dragon Well), one of the most famous teas in China, is grown. What’s more, we had heard that the picking of the highly valued first flush had just begun and if we visited the right pickers we might be able to buy some at an affordable price. Luckily there was a bus stop just near the hostel along the West Lake road and about half an hour later a bus with some vines painted onto its side pulled up – so we were pretty sure it was the right one. We weren’t entirely confident as to where we should get off so we slightly winged it and travelled through a few villages, where we could see people returning from their early morning tea pickings with the leaves balanced in baskets on their heads. About 10 minutes later, the bus stopped ascending and the land flattened out with miles and miles of tea plantations before us. The bus came to a stop and as we realised we were almost the on only ones left on it, we decided that this was as good a spot as any to explore from. It was the right choice as we found ourselves conveniently outside the Green Tea restaurant, which we had heard about from someone in Shanghai. The queues outside were already forming so we decided to take a ticket and try it out.

We were glad we joined the queue early as it continued to grow until early afternoon. We found the location slightly better than the food but the menu choice and variety is pretty unbeatable and the free green tea on tap enriched the view of endless rows of tea-bushes that we could see from our table.

We were glad we joined the queue early as it continued to grow until early afternoon. We found the location slightly better than the food but the menu choice and variety is pretty unbeatable and the free green tea on tap enriched the view of endless rows of tea-bushes that we could see from our table.

The more interesting items on the menu were Deep Fried Shredded Lotus, Spicy Bullfrog, Traditional Style Braised Duck Feet and Tea Tree Mushroom Stir Fry. We went for the Green Tea Roast Chicken (which was absolutely delicious, seeing as we had been mainly surviving on noodles for a couple of days by that point), followed by stuffed tomatoes and a mixture of boiled vegetables and potato.

The Green tea restaurant sits next to the National China Tea Museum, which is attached to a tea school and teaching rooms for those studying tea at university! Tea is taken pretty seriously here (you get the impression that they’d heavily disapprove of a bag of PG Tips or Tetley’s) and as well as a centre of learning the nearby fields are also a very popular backdrop for bridal photography – I think we saw about five or six different bridal parties all jostling for the best position while we made our way through the tea fields.

The Tea Museum itself contains a wealth of information which we are woefully ignorant of in the tea-drinking West, surprising when you consider how culturally important tea has become in Britain, at least. As we were coming out of season, we arrived to find the museum half empty and were greeted by a resident tea expert who took us to a back room full of glass teapots and kettles. She showed us many of the traditional tea preparation methods and allowed us to sample a wide variety of teas that they grow in the research plots in the museum.

The Tea Museum itself contains a wealth of information which we are woefully ignorant of in the tea-drinking West, surprising when you consider how culturally important tea has become in Britain, at least. As we were coming out of season, we arrived to find the museum half empty and were greeted by a resident tea expert who took us to a back room full of glass teapots and kettles. She showed us many of the traditional tea preparation methods and allowed us to sample a wide variety of teas that they grow in the research plots in the museum.

One difference that she pointed out between tea preparation in China and Europe is that the Chinese always fill the entire pot once and empty it before brewing the tea for real. This ‘rinses’ any nasty taste from the outside of the tea leaves and warms the pot before allowing the tea to soak and release its real flavours. Different kinds of tea also need brewing for different times, and some black teas can be refilled over 10 times, yielding different combinations of flavours each time you pour.

Green tea drinkers also tend to drink the tea with the leaves in the glass (whether the tea leaves float or not is a matter of good luck!) and much care and attention goes into choosing the right blend for the mood and social setting, much as a wine would be selected in Europe. Green tea is by far the most popular kind of tea, followed by Black tea and then Oolong tea, which is often confused for the same but has a different method of harvesting and preparation!

Leaf tea and ‘tea cakes’ (compressed tea leaves) are much more popular than tea bags here in China (especially as most Western tea bags are bleached before being filled with tea!), and most of the teapots we saw for sale at the museum had built-in filters to catch the tea leaves and stop the larger ones from escaping into your teapot.

Leaf tea and ‘tea cakes’ (compressed tea leaves) are much more popular than tea bags here in China (especially as most Western tea bags are bleached before being filled with tea!), and most of the teapots we saw for sale at the museum had built-in filters to catch the tea leaves and stop the larger ones from escaping into your teapot.

The last part of the museum focuses on traditional methods of tea preparation and serving across different regions in China. There was some time spent on the Gongfu tea preparation method that we came across in Hong Kong, and also some rooms decorated in traditional styles for serving tea (my favourite was the butter tea commonly served in Tibet).

Despite the wealth of information and the natural beauty of the surrounding fields there wasn’t much actual picking going on and we couldn’t find any tea to buy apart from the overpriced, nicely packaged boxes in the museum (which we had a feeling were all from last year’s crop). The sun was beginning to set so we decided to continue our journey up to the hills again the following day, staying on the bus about ten or fifteen minutes longer in an attempt to track down some of the real ‘first flush’.

Despite the wealth of information and the natural beauty of the surrounding fields there wasn’t much actual picking going on and we couldn’t find any tea to buy apart from the overpriced, nicely packaged boxes in the museum (which we had a feeling were all from last year’s crop). The sun was beginning to set so we decided to continue our journey up to the hills again the following day, staying on the bus about ten or fifteen minutes longer in an attempt to track down some of the real ‘first flush’.

In contrast to the day before it was a very wet morning but that didn’t dampen our excitement at finally finding what we thought was Lonjing itself and its fields and fields of tea bushes, each being carefully pruned by about twenty or thirty pickers in straw hats. We walked through the beautiful plantations where swifts were darting in and around the bemused pickers, until we found a nearby village (which we found out was not Lonjing but somewhere in between). This actually worked in our favour as there were no tourists here and at one of the local tea houses, with the aid of phrasebooks and hand gestures, we therefore managed to procure a small tin of the ‘first flush’ tea (at a negotiable price) which would keep us going through the rest of the journey. We also found a small heat-resistant water bottle with a tea filter built in, which allowed us to make leaf tea from our supply on the move for the rest of the long journey home.

We spent the rest of the day walking amongst fields of tea leaves as the rain cleared, which is a surreal experience for those unaccustomed to the sight. The organised rows of trimmed tea bushes (which would grow into entire trees if left on their own) have an effect on the landscape unlike any other, allowing you to see across the undulating hills for miles around, each one lined with little rows of different shades of green.

We spent the rest of the day walking amongst fields of tea leaves as the rain cleared, which is a surreal experience for those unaccustomed to the sight. The organised rows of trimmed tea bushes (which would grow into entire trees if left on their own) have an effect on the landscape unlike any other, allowing you to see across the undulating hills for miles around, each one lined with little rows of different shades of green.

Pickers from the local villages (each village collective manages a plot of tea bushes and collects the harvest) walk between the rows and hand-pick the fully-grown leaves. All the picking is done by hand rather than machine as this preserves the tea’s flavour and makes sure that all the juices stay inside the leaves until the moment they are pressed (mechanical pickers, while allowing cheaper production, tend to damage the leaves and impair the taste and quality of the resulting tea).

At dusk, we returned to the West Lake in preparation for our onwards journey North the next day. The boatmen who ferry people around the lake all day were making their way back home to their various docks. Seeing the sun set behind the silhouette of the nearby mountains and watching the tiniest ripples float across the lake was a beautiful way to end our time here. We made the most of the peace and tranquility because our next stop would be Beijing, the starting point of our long journey home through Russia…

Great article and I loved the photographs. I’ll go and put the kettle on …